Richard Weston BA(1st Hons), BArch, MLA(Penn), RIBA

Visiting Professor of Surface Design, Cardiff School of Art and Design

Principal, Richard Weston Studio

Director, CreateForAll Limited Molly’s World CIC

Introduction

After thirty years of university teaching, latterly as the Professor of Architecture at Cardiff University, I took early retirement in 2013 to pursue design research interests that could not be accommodated in the UK’s rigid Research Excellence Framework. I work from home and this has proved both personally satisfying and productive. I now hope to move my design studio and app businesses to the USA, where I believe I will have greater opportunities to develop their potential. Much of my recent work grows from what I call ‘Data From Nature’. These have yielded best-selling ‘mineral scarves’ for Liberty of London, interior and architectural applications, and the development of creative apps, for which I employ a full-time coder, Joe Offside. I am writing a book entitled ‘Surface Matters’, to be published by Lund Humphries in 2024. For further details, please read on or visit the following:

Academic Career

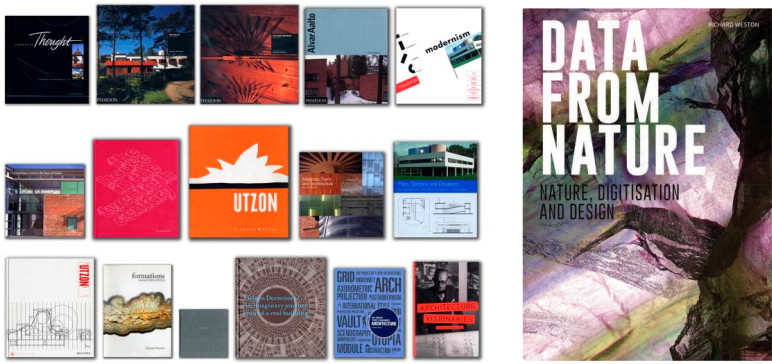

After graduating with First Class Honours in Architecture from Manchester University, I won a Thouron Award to study for a Masters in Landscape Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania. After a period in practice in the UK I was appointed as a Lecturer at the Welsh School of Architecture. Posts in Leicester and Portsmouth (as Head of School) followed, before I returned to Cardiff in 1999 as a Research Professor; I was appointed to the Chair of Architecture in 2005. I edited the UK’s leading research journal, Architectural Research Quarterly (Cambridge University Press), and became a well known author. My books include a Sir Banister Fletcher prize-winning monograph on Alvar Aalto; Modernism, which won the AIA International Book Award; and the only monograph on Jørn Utzon written with access to the architect and his archive, described by a reviewer as ‘possibly the finest architectural monograph ever published’.

Personal Statement: in search of order

I am conscious that the range of the work described below strikes some as bewilderingly diverse. To me, a golden thread links all the projects: a love of nature and a fascination with the organising principles that underpin its glorious diversity.

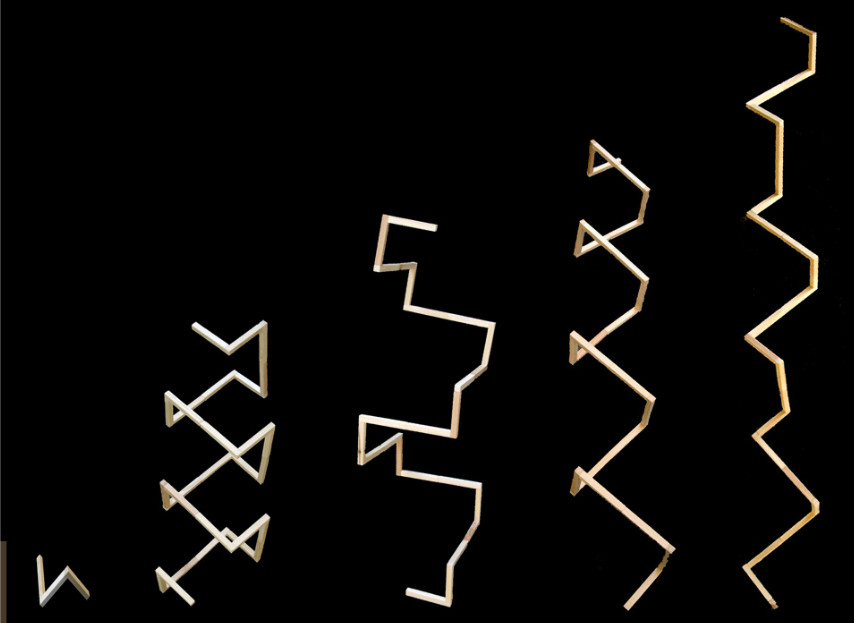

I was introduced to architecture at Manchester University by Esmail Baniassad, who went on to become an eminent international educator (sadly, he died at the age of eighty-six earlier this year). Bani’s teaching was grounded in systems theory and he encouraged us to understand architecture as the resolution of often competing demands, and to search for an inner order for which nature provided an analogue. An early project he set was to ‘devise a component that together with other identical components generates three-dimensional structures’. My response is illustrated opposite.

I finished several days before the deadline and another tutor, not attuned to Bani’s way of thinking, suggested I make freer, more ‘sculptural’ forms with the component: ‘There’s nothing of you here’, he observed. I thought that was the point, and my perplexity was relieved when Bani toured the studio after normal teaching hours, and after a brief explanation declared my response ‘wonderful’ and advised me to submit the work as it was. Partly no doubt as a result of the helical forms the component generated, it brought DNA to mind, and I grasped the idea that a public art like architecture must ultimately rest on an inner sense of order, independent of the whims of its designer.

For all its ‘variousness’, the work of Le Corbusier, who seemed to me then and seems to me now, to be the greatest person ever to pick up a tee-square, was rooted in a love of nature and history. But in my academic research I was drawn to the less well-trodden ground of Aalto and Utzon whose work, so deeply informed by the Nordic love of nature, still has much to teach.

This runs through everything that follows. Early work in my own name grew out of the then (early 1990s) largely untapped potential of glass as a structural material, and I later explored the ‘nature’ and expressive possibilities of materials in a book entitled Materials, Form and Architecture. In her review, Christine Hawley described this as ‘an essential reference for the future’, and the American Society of Librarians suggested it might be an alternative to Rasmussen’s Experiencing Architecture as an introduction for first year students.

My current work rest on sharing the love of nature, vital to a sustainable culture, with chilldren through apps, and to designing buildings and gardens rich in visual delight for humans, and replete with opportunities for inhabitation by other organisms with whom we share Planet Earth. This will be explored in Surface Matters, to be co-authored with one of my most talented former students, Phil Coffey, principal of Coffey Architects with whom I collaborate as a free-thinking consultant.

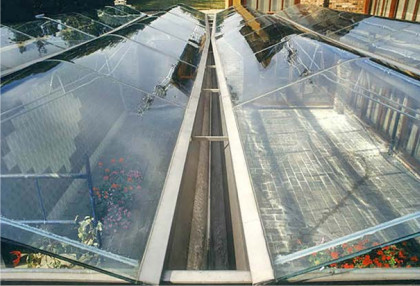

Glass roof, 1992: laminated glass arches span between ‘gutter trusses’ which taper like a river

Radiant House, 1994: the 5.5 tonne stressed skin ply roof floats on 15mm toughened glass

Data From Nature

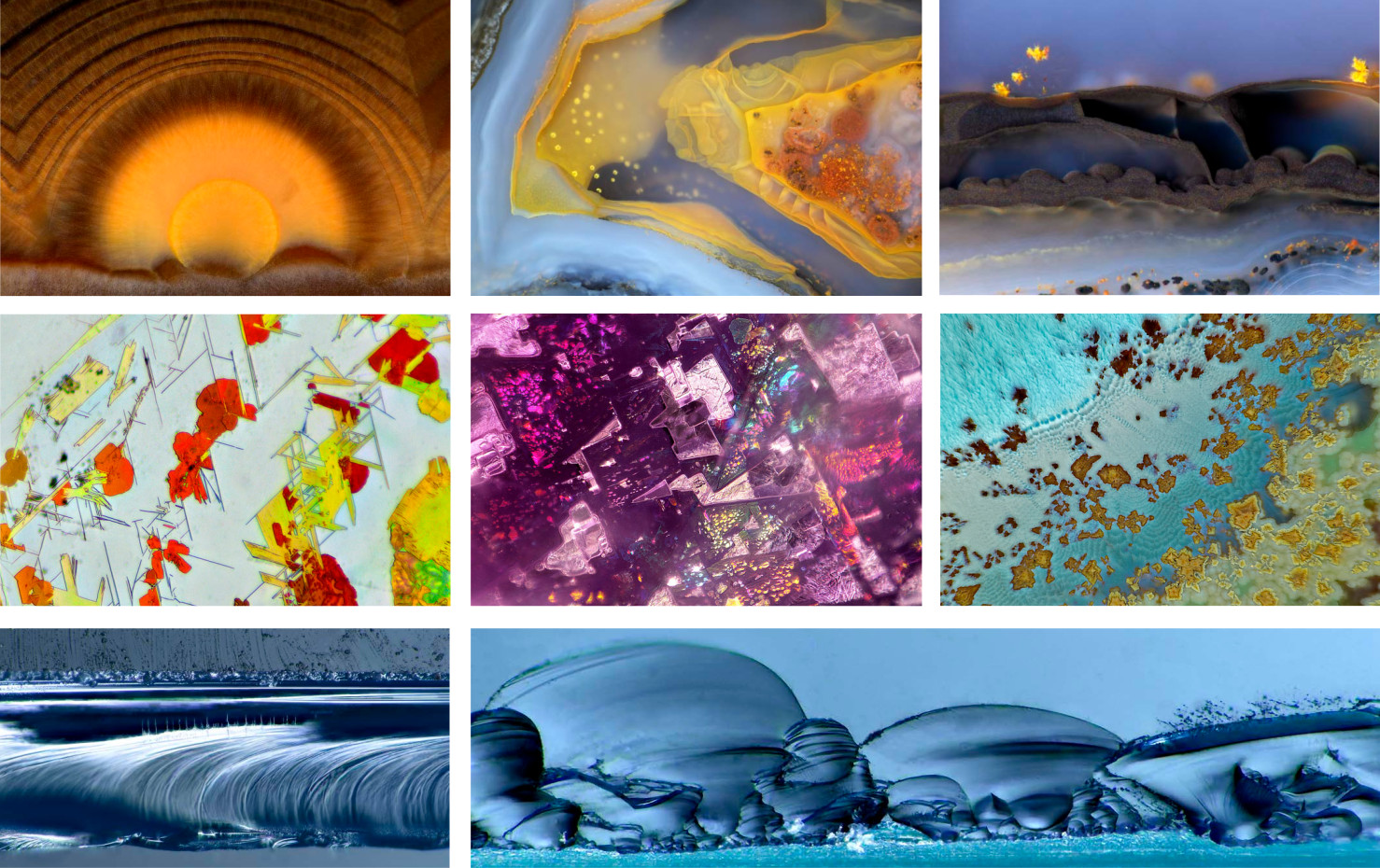

In 2003 I began scanning the cut surfaces of minerals and fossils. The images were equisite and launched me into several years of work capturing what I came to call ‘Data From Nature’. I later bought a £25k Nikon microscope to delve deeper into the magical world of materials. Below, agate; middle: mica, fluorite and ceramic glaze; bottom: glass.

Data From Nature: applications

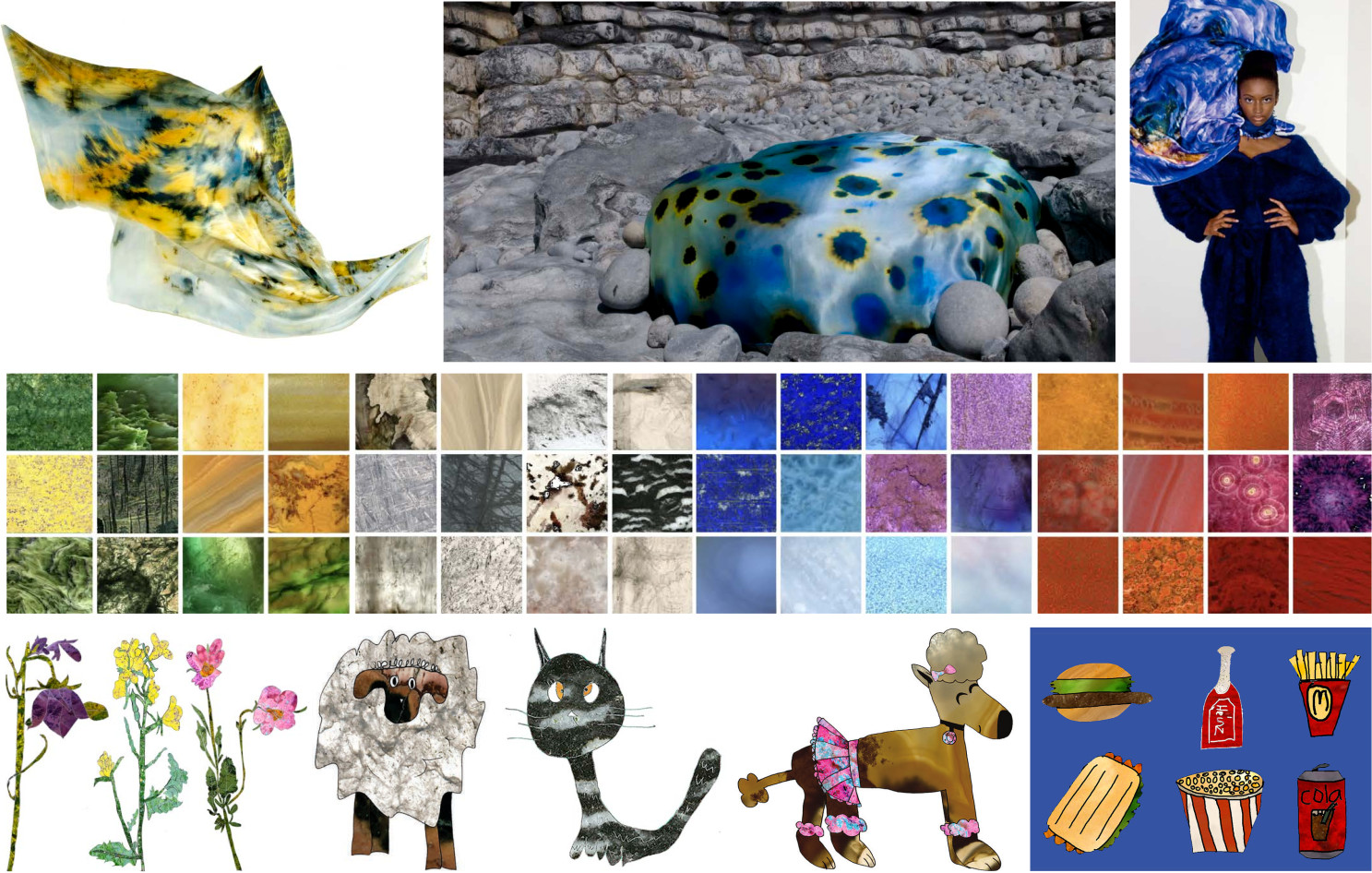

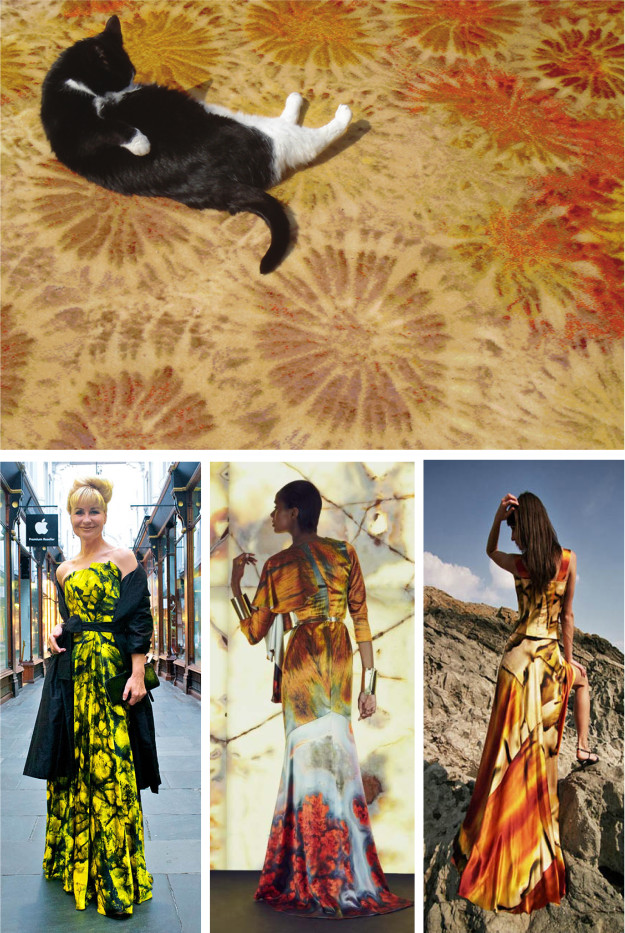

The first application was a range of ‘mineral scarves’ for Liberty of London, launched in 2010 and covered at length in a BBC tv series, ‘Britain’s Next Big Thing’. I went on to to work with children to explore using less ‘glamorous’ colour-field images as ‘digital paints’.

Data From Nature: other applications

Right: Facade of house by Patel Taylor Architects (winner of the Sunday Times’ ‘Small House of the Year Award’ for 2013.

Below: digitally woven fossil coral rug for Gill Tordoff; three ‘Frocks from Rocks’ from olivine, golden plume agate, and mookaite.

Data From Nature: images and VR ‘worlds’

The images below are captured from the surfaces of calcite rhomboid crystals (I have several thousand), while those along the bottom are screen-shots of 3D ‘worlds’ processed from ‘vertical stacks’ of images taken as little as 1 micron apart from cracks in the specimen of agate shown. The source .wrl files can be processed to create full VR environments: click the specimen of chalcedony to the right to see a less processing-intensive one-minute video ‘tour’ of the model shown. I am about to buy an Apple computer capable of processing full VR files for a project I call ‘Gardens of the Mind’.

App development

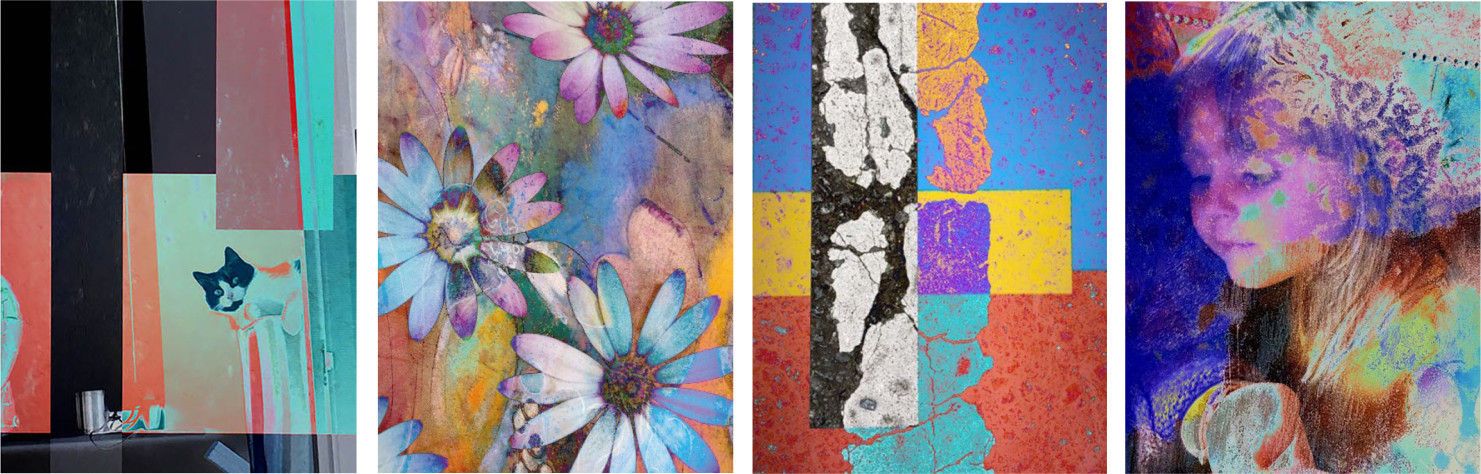

After working with children using Photoshop and my digital paints, I realised that a painting app could open the process to any child. Using the best of the images inspired by my cat Molly, the MollyApp emerged, soon followed by the educational website Molly’s World. Linked to digital manufacturers, the app enables children to create their own material world of fabrics, clothes, wallpapers, mugs... The website is due for launch in October, but can be viewed at www.mollysworld.org.

Molly’s World shows the way forward, not only for visual education, but for all learning.

Richard Hickman, Emeritus Professor, Faculty of Education, Cambridge University.

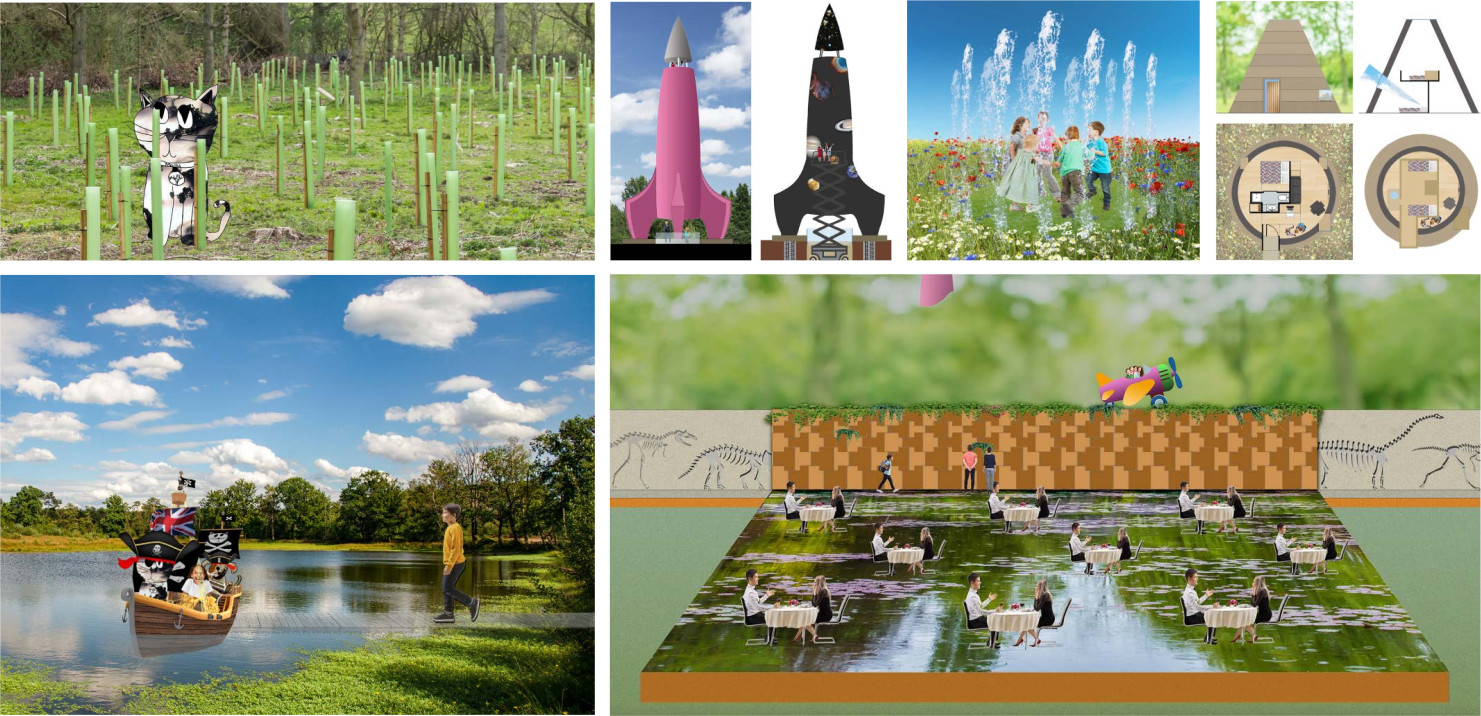

Sustainability

Beginning with Antarctica, supported by a grant for outreach from the US National Science Foundation, we are running five projects: a tree-planting scheme that has already begun in Nigeria, and others on meadows, coral reefs, and ocean pollution. We have expert advisers for each and will use children’s work to campaign publicly.

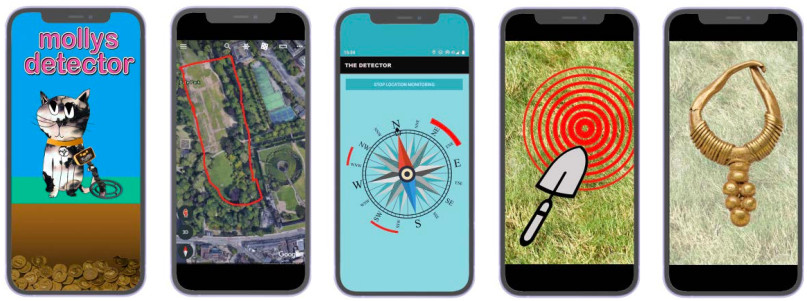

Detector app

This is essentially a GPS-based location system, whose first application will be a game that simulates the process of metal detecting. This is being developed in collaboration with Keith Westcott, who will shortly launch a new Institute of Detectorists and archaeological charity. Keith is a member of the popular ‘Time Team’ which commands a million loyal followers on YouTube.

We are also working with a local tourist attraction, Fonmon Castle, to explore the app’s potential as a guide to historic sites.

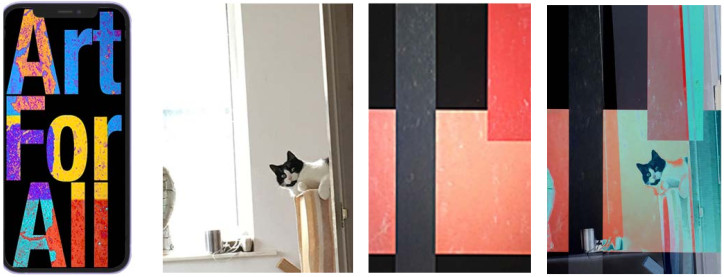

ArtForAll app

This app fuses a snap taken on a phone with a digital file that may be downloaded from the Web or added using the phone. Many ‘blends’ are awful, but if you persist it can yield beautiful things: in the digital age, judgement not traditional skills are allimportant. ArtForAll will be launched alongside the MollyApp, which includes the same funtion.

Garden design

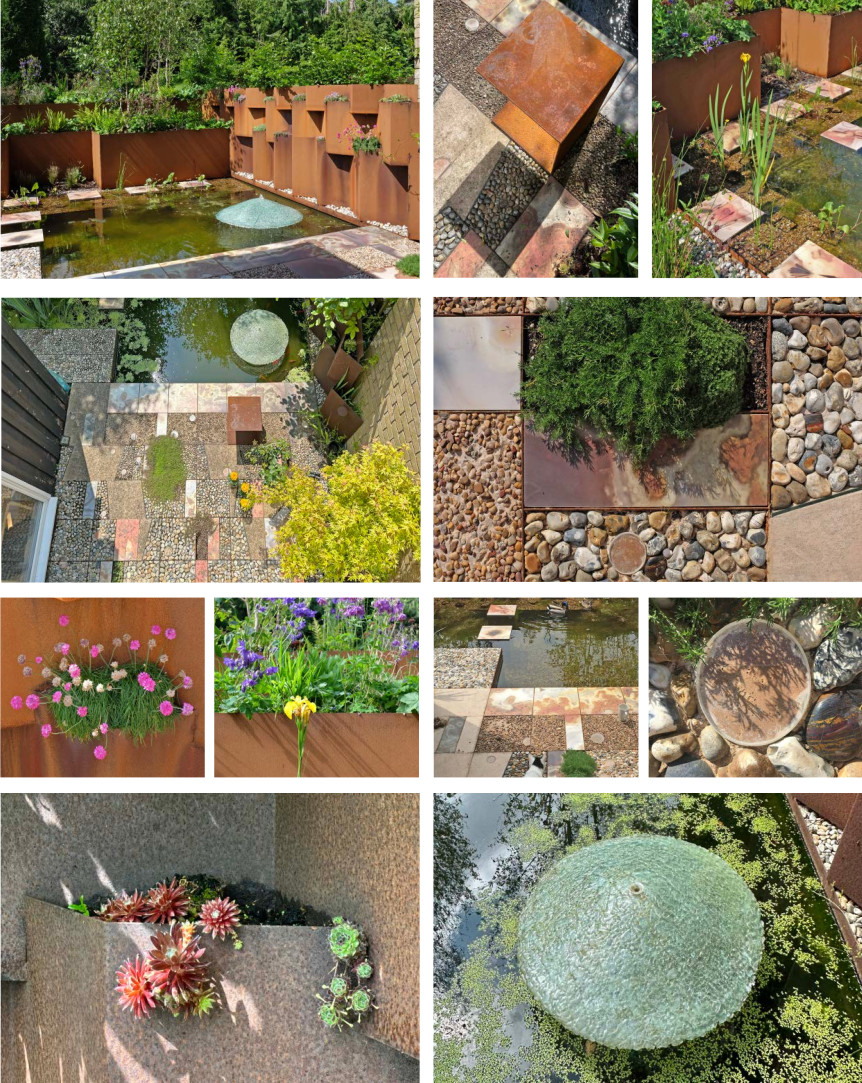

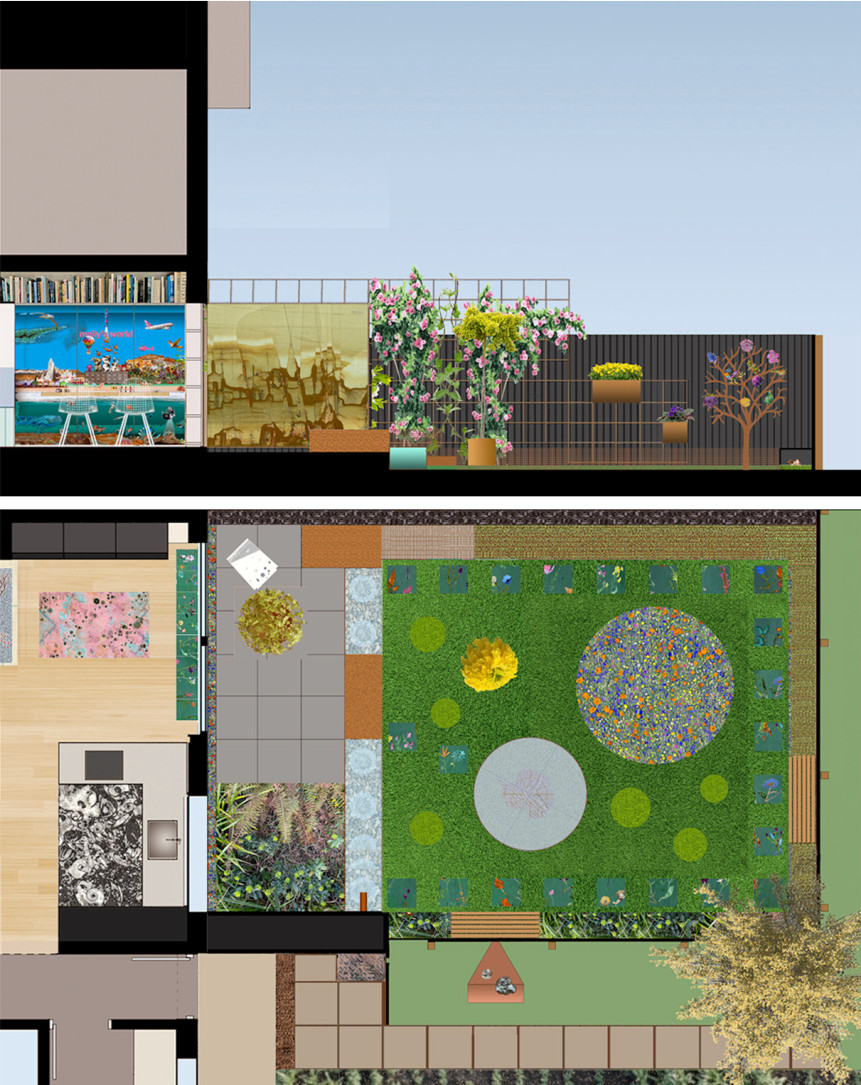

My house, in a quiet close, came with a front garden of sloping lawn and shrubs along the pavement. Following retirement from academe I decided on a major transformation. In 2021 it was featured on the BBC’s flagship ‘Gardeners’ World’: to view, click here.

The house sits 900mm below the pavement and the new patio enjoys direct sun from 11.00am until early evening. The space is structured by low retaining ‘walls’ which peel off the three diminishing levels of a folded-plate ‘steel cliff’ that frames the pond. ‘Stepping tiles’ printed with images from a Moroccan agate provide access for maintenance, and a ‘Glass Volcano’, made of fused shards of recycled glass, aerates the water. Twenty goldfish have grown into a shoal of sixty.

An invisible grid, based on the square tiles, runs across the pond and materialises on the patio as a shallow steel frame, variously filled with pebbles, graded from small to large, as on a beach; small tumbled minerals and shells; rhomboidal areas of concrete; and patches of camomile. The tiles are printed with an image captured from 2cm of a Hungarian agate that resembles a coastline seen from the air: they frame the pond edge and the image underlies the whole patio, but only appears as a few narrow, rectangular tiles. Scattered apparently randomly through the grid are discs of glass. These follow the pattern of high-magnitude stars on my birthday and in low winter sun reflect a constellation of sunspots onto the living room ceiling.

The planting adjacent to the road is mostly early successional, with single multi-stem Himalayan Birches and occasional splashes of colour. Yellow flag iris blaze briefly at the narrow end of the pond, and marsh marigolds add more yellow. Succulents and sea thrift are planted in the triangular pockets created by the staggered layers of the ‘cliff’.

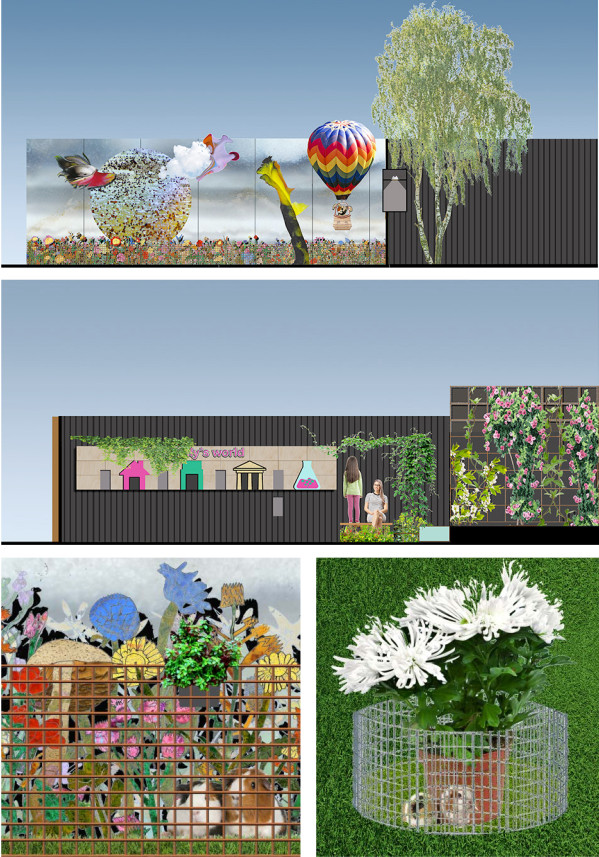

MollyGarden

As I write (18 July, 2023), work has just started on the back/‘Molly’ garden. It is designed to remind children of the website and celebrate their use of the MollyApp: flowers, birds and insects can be fixed with magnets to steel trellises and a ‘Tree of Life’. The lawn is a poke in the eye for Chelsea orthodoxy which berates mown grass (where are children to play in their oh so designerly world?). It will be allowed to welcome buttercups and daisies, and the neat grass circles will be ‘mown’ by guinea pigs, who also have a sheltered run along two sides.

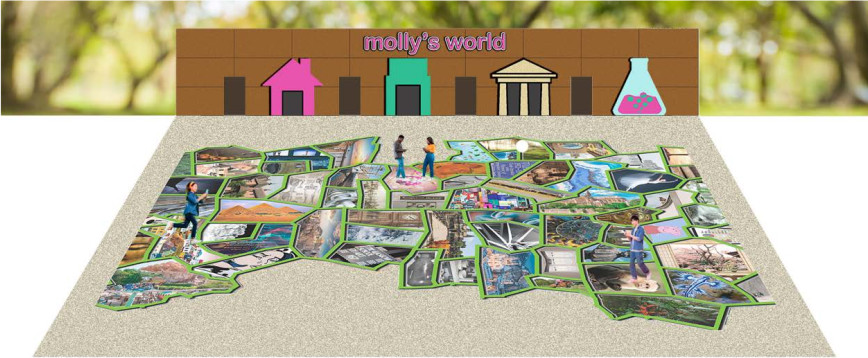

Molly Centres

Molly Centres will be to Molly’s World what Disneyland is to Disney: places filled with locations familiar from the website. They will combine bio-diverse habitats – woodland, pond and meadow – with opportunites for play combined with ‘maintenance’: the fountains in the meadow are activated by motion detectors to trap children and water the ground. The MollyRocket will double as viewing tower, and tell stories about the universe, told with projections as you slowly ascend on a scissor-lift. The Fields of Knowledge, framed by workshops and exhibition spaces, will materialise as a mosaic to be navigated with the Detector app. A formal lily-pond will offer unique dining opportunities, with tables supported by fritted glass, all but invisible just below the water surface. The natural pond will offer a photo-opportunity aboard PirateshipMolly. Conical glamping shelters will be 3D-printed using an overhead gantry and robot arm dispensing subsoil mixed with water.

Garden design: ‘California Dreaming’

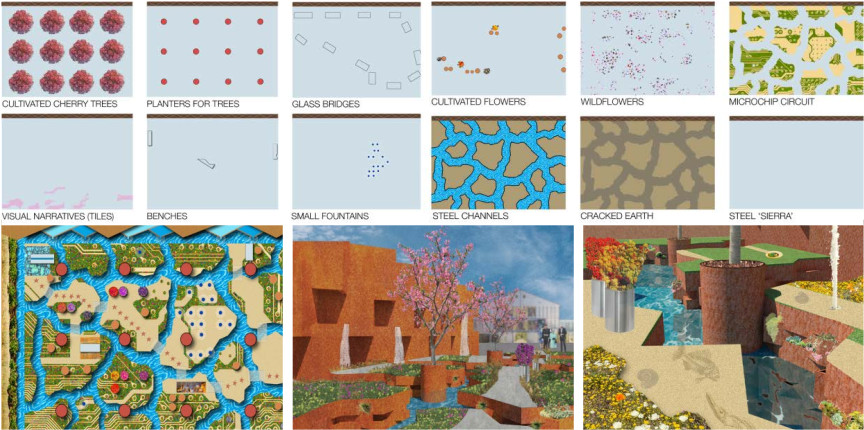

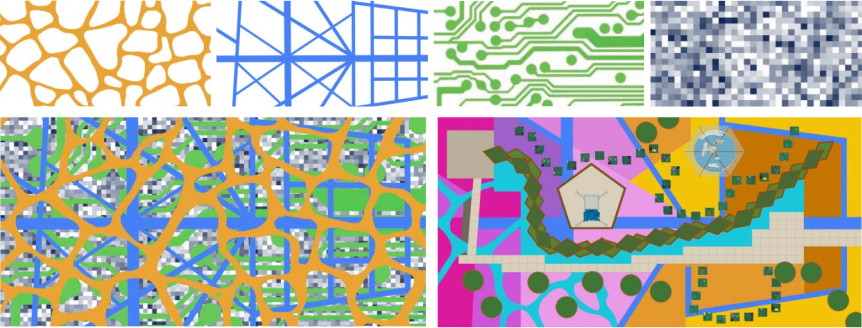

My approach to garden design harks back to Ian McHarg’s ecological ‘layer cake’, with a nod to the work of Peter Eisenman and others in its use of formal layering. In place of mapping the site’s geology, soils, etc., I use relevant ‘cultural’ data. The approach was tested with a theoretical project ‘California Dreaming’, a potential show garden for the Chelsear Flower Show (right), which I still hope might attract a wealthy ‘tech’ sponsor.

‘Gifts from China’

I have been asked by a Chinese client to propose ideas for a garden for the 2025 Chelsea show. These celebrate China’s role as a stimulus to the informality of the English Landscape Garden, and source of native plants whose cultivars are now found in garden centres across the UK.

The design deploys a section of ‘steel cliff’, which echoes the plan of the Great Wall near Beijing, set on a plan distilled from cracked earth, the plan of Versailles, a printed circuit board, and a pixel grid that materialises as printed tiles and concrete paviours.

Chelsea gardens cannot be entered by visitors, and their first glimpse will be through a large aquarium, ‘aquascaped’ with intricate ‘scholars rocks’ to re-create a scene like that below outside the village of Pekkinsa, illustrated in a Dutch book published in 1675. The convoluted forms of the limestone – products of the coral sea that covered Suzhou – were enhanced by sculptors.

Archive: competitions and commissions

Public artwork, Hamilton near Glasgow (competition, 2nd prize, 1999)

Sundial for Menna Richards, Controller of BBC Wales (2003)

Water Garden (project, 1993). Intended to be built in a redundant water tank next to the glass roof illustrated above, the project had to be abandoned when the client needed the money to buy an adjacent house for his elderly father

National Wildflower Centre (short-listed competition entry, 1998).

Exley House (project, 1996): a week-end house to be built adjacent to houses by Berthold Lubetkin just over the fence from Whipsnade Zoo (refused Planning Permission due to Green Belt restrictions).

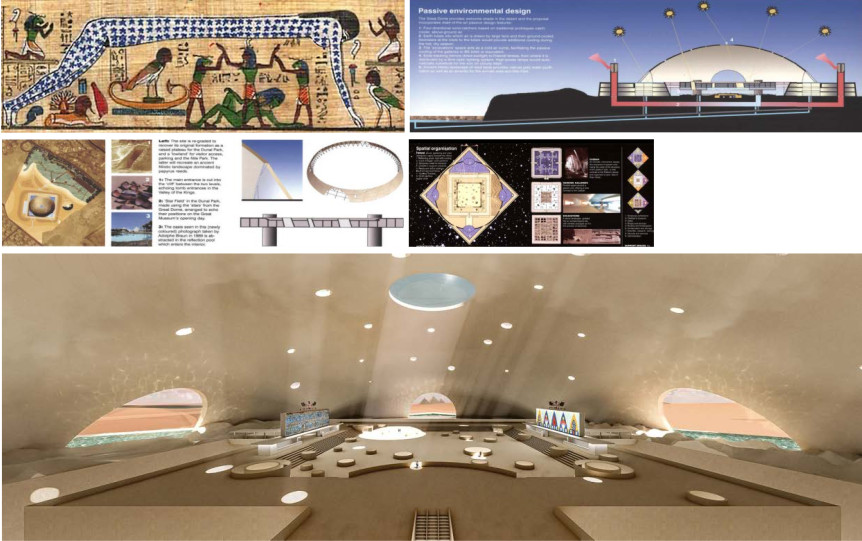

Grand Egyptian Museum (competiton, 2002). Located on a site addressing the Giza pyramids a mile away, I proposed the world’s largest stone-vaulted space as a counterpoint to the largest manmade solid. The eggshell-thin dome dome was inspired by the Ancient Egyptian depiction of Nut, the Queen of the Night, as a vault of stars sheltering earthly life below. It acted as a vast sunshade for a largely passively controlled space, and was pierced by circular openings, sized and placed according to the magnitude of the stars overhead. The resulting sunspots were plotted and, at places of maximum overlap, ‘carved’ voids through the galleries, suspended in cooled air, down to the required re-creation of the tomb of Tutankhamun. A concete labyrinth would have stored cool air in the winter, and the compressive loads at the base of the dome came close to – but happily would not have exceeded – the crushing strength of the limestone.